Thanks to the efforts of a professor and her research assistants, data on how lead contamination has affected the younger populations in York City is being analyzed and adapted into an interactive StoryMap. The team hopes to bring greater attention to the issue and the number of affected individuals.

According to an article published by the York College of Pennsylvania Center for Community Engagement (CCE) Urban Collaborative, lead poisoning is a serious problem that has been affecting York City since the 1900s.

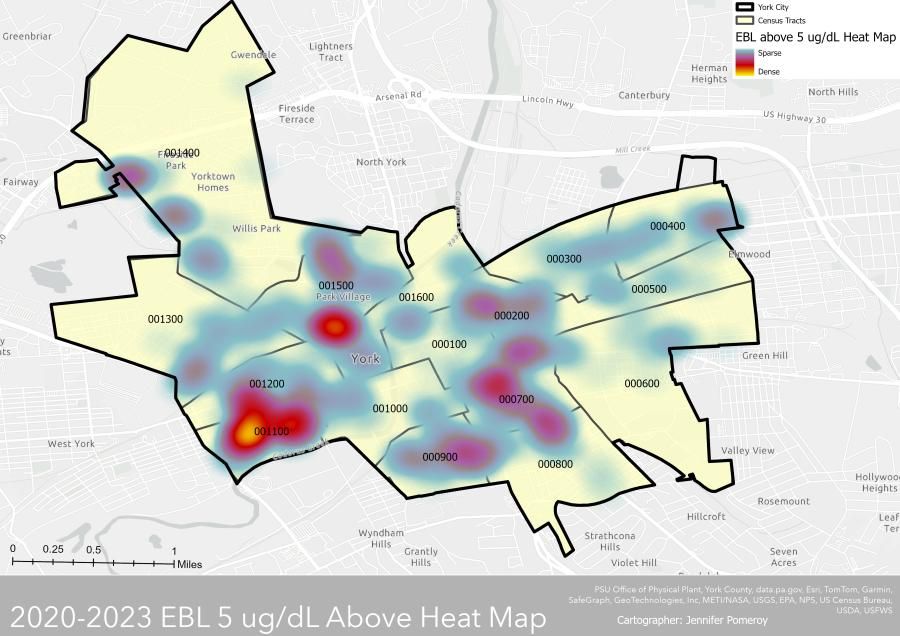

Dr. Jennifer Pomeroy, Associate Professor of Geography, hopes to raise more awareness through her research on elevated blood lead levels (EBLLs) in York City. She aims to create a “hotspot” map detailing which areas/neighborhoods within York City have the highest concentrations and share the data with the local communities. Hopefully, the impact of lead contamination will decrease as people become more aware and take immediate action to protect themselves, their loved ones, and the community.

The Invisible Threat

How does lead contamination happen? For many parts of the community, it happens at home.

Many of the buildings in York City were built in the early 1900s, and as a result, lead paint was often used. It was advertised as a “long-lasting and permanent” paint that was both durable and affordable. Frequent advertisements for them were common, and soon, other items, such as furniture and even children’s toys, began to use them later.

As time passed, however, these buildings began to age, and the lead paint started to chip. This resulted in lead getting in the air and dust, creating a high-risk environment for the people who lived there, especially children. Even if young infants weren’t putting lead-painted toys and objects in their mouths, the air, food, and water could be just as harmful from airborne contamination, negatively affecting them during a highly vulnerable time in their longitudinal development.

One of the main reasons why the connection isn’t often made is that not enough children get tested for exposure before negative behaviors or neurological issues surface. While it is not possible to completely cure a child from lead poisoning, early diagnosis and identification of the root cause would allow for more effective intervention and reduce risk.

Creating a Plan

Dr. Pomeroy became involved with addressing the issue during a conversation with Carly Legg Wood, Director of the Urban Collaborative, in the late summer of 2024.

While discussing another project Dr. Pomeroy had been working on in the past, the topic shifted to the lead poisoning problem in York City.

When Dr. Pomeroy expressed interest in doing a study related to the issue, Wood contacted the York City Bureau of Public Health for data she could use. Wood found that they had blood-lead sampling datasets taken from children from 2014-2023, which excited Dr. Pomeroy as they are comprehensive long-term data that reveal consistent patterns once cleaned and pre-processed.

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has created guidelines to prevent lead poisoning among children, it has remained a persistent public health issue, and that is partly due to not having a concrete image of which specific areas need to be addressed.

“We don’t know where exactly the lead poisoning’s worst level within York City is,” Dr. Pomeroy said. “We know it’s there, but York City is a system. So within this system…we want to have a better understanding of that.”

GIS Mapping & Insight

For the study, Dr. Pomeroy examined data on infants and children ages 0-16, the group most affected by lead due to its profound effect on their early development. She specifically looked for any data that indicated an EBLL greater than or equal to five micrograms/deciliter - as stated by the PA Department of Health and CDC at the time.

She planned to spend the 2024 Fall Semester cleaning, pre-processing, and geocoding data for preparation of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) analysis and then using it to create a map series that would eventually display where the major “hotspots” for lead poisoning were. Using GIS software, a map series will be created and published at the end of the 2025 Spring Semester.

To help with such an enormous task, Dr. Pomeroy recruited help from two research assistants.

Helen Paglio ’25, a senior Environmental & Sustainability Studies major, assisted Dr. Pomeroy with creating the initial StoryMap during the 2024 Fall Semester. After taking her G261: Introduction to GIS course, Helen was approached by Dr. Pomeroy about helping her, which gave her more experience working with the GIS software and a chance to explore an important matter with the opportunity to educate the York City community.

The StoryMap contains many interactive components, allowing viewers to engage with the elevated blood lead data and continue to educate themselves further. Census sites and collaborative information from the CCE will be included. The goal is for public awareness, community engagement, and resource mobilization.

“It’s all about being able to reach an audience in a way that resonates with them,” Helen said. “So [the map] tells the story of the history of lead, breaking it down…[and letting] people understand this is a national problem. But in addition to being something so large, it also has a very community-based impact on us.”

Already, they have found two major hot spots close to York College where, according to the sampling data, the children have higher concentrations of elevated blood lead. Male Black children had the most significant number of elevated blood lead numbers. It was even found that the building structures in those areas had been built before 1978, indicating that they had lead paint and chips that could spread contamination.

Spreading Awareness In-Person and On-Stage

Lydia Sanderson ’26, a junior Environmental & Sustainability major with Biology and Outdoor Leadership minors, begins her work as Dr. Pomeroy’s second research assistant this 2025 Spring Semester.

Having taken the professor’s G261: Introduction to GIS class the previous semester, Lydia will be working on the statistical analysis of the data and looking closely at the ages of building structures. This will involve exploring common socioeconomic and other factors that might have contributed to lead contamination, such as being more aware of construction sites near potential hotspots, as building demolition is a common source of lead poisoning.

Dr. Pomeroy hopes that once all of the data is finalized, her team will be able to reach out to some local neighborhoods to educate them about the elevated blood lead sample conclusions they came across.

But the work won’t stop with the lead contamination map. Dr. Pomeroy and Lydia plan to write and publish an academic paper on their findings, allowing them to communicate their results to a greater audience, advance research in public health, and improve public health policies and strategies.

“Right now, we’re still working on the analyses of the different datasets and mapping - that’s what we’re focusing on right now,” Lydia said. “But once all of that is done, probably sometime this semester is when we’ll start writing the paper. And I think [Dr. Pomeroy] said she’s hoping it’ll be done by midsummer, around that time.”

They also plan to attend the 2025 Pennsylvania Geographical Society Annual Conference in November. They aim to submit a scientific poster on a statistical analysis of lead contamination of vulnerability.

An Impactful Experience

The work both Helen and Lydia have done will leave a great impact on the York City community. It has also allowed them to grow their skills, especially when using technology such as GIS to communicate information in an easy-to-understand way.

“GIS is so important, and to gain that experience is really beneficial to me,” Helen said, “because it’s one thing doing GIS in a class with all these theoretical things or with data that’s already been gathered and used for whatever purposes. But to actually apply it really allows for more freedom of exploring the system and the capabilities, and really gaining sort of depth and breadth of skill in that field.”

“I think that having at least knowledge of how I can, in whatever job I am in…work with [GIS] specialist[s] more effectively based on the knowledge I have of GIS and of its ability and uses, and how to apply research to the GIS application, I can be more effective in whatever role I have,” Helen continued.

Overall, they hope their work will usher in a new wave of action against lead contamination in York City. Even if it is just raising awareness about the issue, creating such an essential resource for the community will have a lasting effect that will help many young people.

“I don’t live in York City. I live outside - I’m a commuter, but I didn’t even know that York City had a lead problem or that was something that was going on,” Lydia said. “I feel like this project could help inform the public about lead poisoning that’s taking place in York City so that they’re made aware of it, and they can get their homes tested or take precautions when it comes to that.”